The romance of neoliberal peasant farming blinds us to our collective power

Let’s get this out of the way, first:

- I am a small farmer, operating on 40-ish acres in Virginia’s Northern Neck.

- I am not paid by, in-hoc to, in league with, or particularly happy with ‘big agriculture.’ I’m just a guy who’s been in the small-sustainable farming business long enough to understand that the model is fatally flawed, and mature enough to say it out loud.

- To my friends that run and staff far

Now…

I recently found myself with the free time to do some simple math. One of the larger farmers markets I participate in has about 100 vendors. I’m one of the mid-sized operations that sells there, and I’m paying about $1,000/year in fees to participate in the market. I’m also devoting about 250 hrs/year in staffing and prep time (call it $3,000), and about $650 in fuel getting to and from the market, plus another $1,200 in wear and tear on my vehicles.

Altogether, then, I’m paying $5,850 to participate in a large farmers market.

It’s pretty safe to assume that the costs of the other 99 vendors are similar. We’re shelling out a combined $585,000 to participate in just one market. Most of us participate in at least two markets, so let’s double the figure to $1.17m, then round down to $1 million just to be conservative.

A $1 million+ annual operating budget could comfortably lease, service, and staff a large urban brick and mortar market that’s open 12 hours a day, 7 days a week, year-round.

Instead, we spend it on a pop-up market that’s open just half the year (in my neck of the woods), for two days a week (remember, two markets), four hours at a time. And it’s probably outdoors — where rain, excessive heat, or a cold snap will effectively ruin your day.

As much as I like farmers markets, the amount of resources that small farmers pour into them is terribly misdirected if we’re serious about mounting a real challenge to the conventional food system.

The cultural power of farmers markets is a symptom of what’s fundamentally wrong with sustainable/regenerative agriculture: veneration of the small family farm. It’s the sacred cow of American cultural identity dating back at least to Thomas Jefferson’s dream of a nation of yeoman farmers.

Only thing I regret about the past: not being there to wear them sweet duds

America’s oldest farmers — indigenous people — generally regarded the soil as a commons and worked it cooperatively. Many indigenous nations, along with a number of religious and ethnic communities, continue the practice to this day. But the notion of the private farm, be it a pair of greenhouses or tens of thousands of acres, is what came to dominate American farming, and it’s taken particular hold among the farm to table cohort.

We in that cohort trade the benefits of agrarian collectivism — living wages, retirement, a sane workload, profitability, survivability, and the capacity to make a game-changing impact in the marketplace… for rugged independence: complete autonomy in decision-making, the ability to grow what/where/how we want, set our prices as we please, sell wherever we choose, and work ourselves into the ground.

In short, we’ve done the most Modern-American thing possible: bartered away our quality of life for the freedom to be miserable.

Our freedom also costs us results in the marketplace. The zeal for “saving the world” is undercut by annual sales at farmers markets estimated at less than $2 billion in the U.S., with the growth of markets slowing even as hundreds of billions of dollars of food is sold annually in grocery stores. As the link above states, part of this slowdown may be the result of an explosion in local food hubs, which are themselves riddled with competitive issues of their own, in addition to (generally) being non-farmer owned and little more than middlemen that force farmers to take prices.

Note: “Small family farm” does not mean they’re farm-to-table outfits like mine. Most small farms are producing for the big commodity markets just like the big guys.

Because of our insistence on independence and our failure to cooperate more closely, we’re being outsold at the grocery store by a factor of 400+. Accounting for on-farm, food hub, restaurant, and other non-market sales does little to affect the scale of this imbalance. Farmers markets and other “local” outlets punch well above their weight in terms of social/cultural value, but this is fooling us into believing we’re making more of an impact than we actually are, and that a rapidly consolidating food system backed by venture capital, entrenched interests, and the world’s wealthiest corporations will somehow be displaced by the romance of neoliberal peasant farming.

Go to a big farmers market this weekend and have a look around. Each of those independent producers would tell you interesting stories: 80+ hour work weeks, getting by without health insurance, paying employees next to nothing and/or relying on volunteers, supplementing with outside jobs. Enduring broken marriages, worn out bodies, social isolation, strained finances, emotional burnout.

These are the conditions my grandfather’s generation endured that convinced their children to get as far away from the farm as possible. The current and relatively young generation of back-to-the-landers, diving into an ocean of nostalgia for pearls that aren’t there, is setting the stage for similar generational exit when their children come of age.

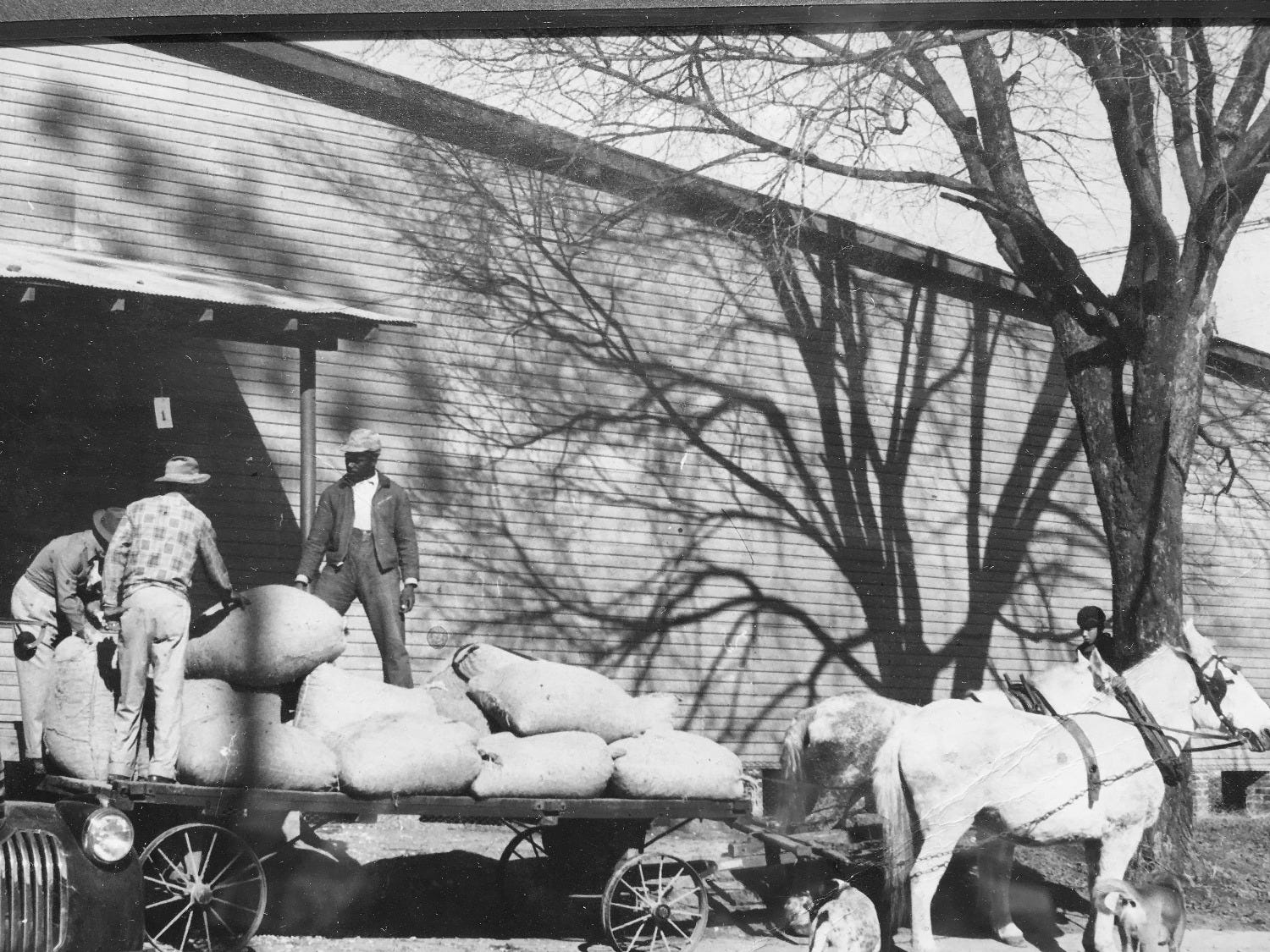

My grandfather (in dark clothing on the wagon facing the camera) hauling a record peanut harvest to market, sometime in the 1930s

Unless, of course, we choose a different way.

Imagine all the producers at that market combining their acreage, expertise, supply chains, and financial resources into a co-op committed to producing food regeneratively, responsibly, and ethically. The results would be astonishing:

- Costs of production would decrease significantly. Orders of seed, feed, equipment, and supplies would no longer just be in bulk, they’d be at regional scale. Labor hours would be reduced as dozens of farmers are no longer replicating the same tasks (e.g. purchasing, bookkeeping, inventory, etc.)

- Marketshare would swell. Owing to lower prices, larger quantities, and more accessible markets (B&M and delivery), we’d be able to service a much larger segment of the market. Increases in volume would reduce overhead costs, more than offsetting the reduction in each unit’s top-line*

- Wages and quality of life for farmers would rise in real terms. The confluence of reduced production costs, cooperative labor, and increased marketshare will mean individual farmers are working less and getting paid more. We’d actually be able to enjoy creature comforts of other industries like evenings and weekends off, PTO, group health insurance, even retirement.

- The barriers to entry for new farmers would be much lower. New farmers would not have to learn to be entrepreneurs, marketers, agritourism experts, and social media mavens in order to make it work. A farmer could actually make a living as a trade journeymxn, just like any other trade, and brand new farmers could be trained by the co-op itself. On a related note…

- Sustainable farming could be de-gentrified, since it would no longer be a “labor of love” only available to people that can afford to work for free or next to nothing (i.e. afford to be exploited, which is a bad thing even if they don’t seem to mind very much). Everyone — people of color in particular — would be able to look at farming as a viable career choice.

- Farmers could follow their passions instead of diversifying. The co-op has producers of livestock, produce, fruit, mushrooms, grain, dairy, flowers, etc. Ecological diversity is managed at the co-op/landscape level rather than the level of the individual producer, so the latter can focus on what they do best, still make a living, and still operate within an ecologically-restorative framework.

- Farmers could operate at the scale they choose. If someone just wants to grow microgreens in their basement and sell them into the co-op’s single payer market, so be it. If they want to range a cattle herd followed by sheep and chickens across a few hundred acres leased or owned by the co-op, go for it. The only constraint is that the producer must follow the co-op’s production standards.

*E.g. — we net more money selling 100 chickens to a single restaurant at a 30% discount than we do to 100 individuals, because that bulk order means we’re not paying for individual storage, transport, potential spoilage, transaction fees, the cost at the point of sale, etc.

The point is, these farmers would no longer be alone. We’d present a united farmer-owned (this is key) interface to the rest of the world — suppliers, customers, landlords, regulators, media, etc. — that, at present, each farmer is left alone to handle. It’s that isolation that makes us weak and ineffective against incredibly well-resourced competition.

We have to evolve if we’re going to survive.

Of course, subscribing to this model is going to take a big mental leap for some farmers because participating in a co-op DOES mean surrendering some autonomy — you have to adhere to the group’s agreed-upon regenerative growing practices (we kinda do this anyway), you don’t get to set your prices (you don’t necessarily have to sell anymore, either; you just get paid a salary), and there may be limits around what gets produced.

The big change is that the farmer isn’t just accountable to themselves; they’re accountable to all the other co-owners. But that accountability goes both ways, and the farmer has both a voice and a vote in an organization that’s big enough to compete, but small enough for each voice and vote to matter.

Without that change, each farmer is left alone and isolated, having to handle their own leases, purchasing, packaging, insurance, taxes, regulatory compliance, customer relationships, marketing, research, technology, bookkeeping, and staffing… to say nothing of doing the full-time job of farming itself. It’s categorically unsustainable, and extractive agricultural interests are counting on it. In particular…

- Farmers being so preoccupied with non-farming tasks that we don’t have the headspace to consider alternatives or act strategically. If we’re working all the time, and are physically and mentally exhausted, we simply don’t have time to think clearly.

- Ecologically extractive agriculture drawing the kind of margins that attracts private investment and capital, while restorative agriculture does not; only throwing off enough profit to benefit the self-investment of the producers. Our competition is relying on the inefficiency of our self-investment (e.g. farmers markets), which is driven by…

- Farmers internalizing the mythic virtue of rugged independence, which keeps us isolated and denies us the efficiency, effectiveness, and power of acting collectively to countermand the efficiency, effectiveness, and power of private capital.

And now that we know this, it’s time to do things differently.

Our farm has access to thousands of acres of land near Washington, D.C., only a fraction of which we’re able to actively farm since there’s only three or four of us. We’ve resolved to evolve our business into a farming collective for all the reasons stated above, with a particular focus on providing opportunities of ownership for people traditionally denied such roles in agriculture: people of color, LGBT folks, and women, in particular.

Aerial image of our broiler chickens, cattle, and laying hens in a field in Virginia’s Northern Neck

The end result will be a group of 75–100 producers stewarding land everywhere from the suburbs of the nation’s capital to the Virginia Piedmont, each one making a living wage and enjoying a high quality of life while our customers enjoy greater access to our products in terms of price, variety, and availability. We want this to become a template for other smallholding regenerative farmers orbiting other cities to follow, so they too can make a real and measurable impact on the land and on the market.

We’ve launched a Kickstarter to prime this effort, and hope you’ll consider making a pledge.

In the meantime, I hope you’ll consider making a trip to your local farmers market. Even in the promised land of farmer-owned brick and mortar markets offering door to door delivery, farmers markets will still be one of the best ways to connect to the actual people growing your food and gain an understanding of what it takes to responsibly feed a hungry planet.

Chris Newman is a farmer in Virginia’s Northern Neck. He’s tall and skinny and is growing a great and woolly beard for totally non-political reasons. If you like what you’ve just read, please consider a click on that there green heart thing. And if you really like what you just read, please consider a pledge to our Kickstarter

Source:https://medium.com/sylvanaquafarms/small-family-farms-arent-the-answer-7...